|

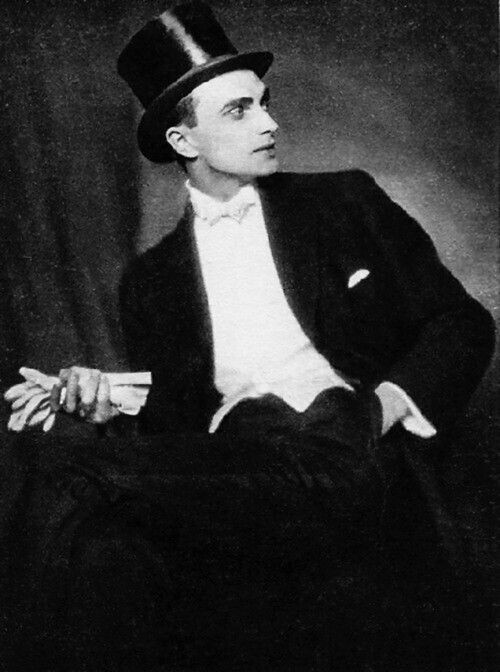

| Conrad Veidt, c. 1920, by Karl Schenker |

Hans Walter Conrad Veidt, affectionately nicknamed Connie, was born 22 January, 1893. There is some discrepancy regarding the exact location of his birth, but it's likely he was born in a residential area of central Berlin. His parents, Phillipp Heinrich Veidt and Amalie Marie Anna (née Göhtz), were members of the late 19th century's ever-growing middle class. They had one other child besides Connie, a boy named Karl, who died at the age of nine shortly after the turn of the century. Herr and Frau Veidt sent their son Connie to school in Schöneberg where, even though he struggled in school and had terrible grades, he briefly imagined himself going into medicine before finally discovering theater in his late teens when he received high praise for his performance in a Christmas school play. Connie technically left school without graduating, but it didn't matter. By then, he was determined to begin his career as an actor.

One of the most prestigious theaters in Berlin was Max Reinhardt's Deutsches Theater. Connie had resolved to attend as many performances there as he could, absorbing the work of the great actors of the early 20th century from the cheap seats. His parents didn't always have the income necessary to fund Connie's trips to the theater, but his mother made sure to have some extra cash on hand to support her son's newfound passion. Connie and his mother Anna doted on one another and were always very close. His relationship with his father was more chilly. Phillipp, a civil servant who died in 1917 right as Connie's stage career was taking off, was fairly conservative. Connie confessed years later that his choosing to work in the arts had been a significant disappointment to his father. But Anna loved her son without exception. Her death in 1922 was profoundly devastating to Connie, and he would go on to say candidly that he never really got over it.

Throughout 1913, Connie spent a lot of time awkwardly hanging around the Deutsches Theater and eventually befriended a staff member who was able to introduce him to a member of Reinhardt's company. This actor offered training sessions and, for a small fee, took Connie on as a student. After several sessions, Connie finally auditioned for Max Reinhardt, performing monologues from Faust. Despite being so green, he must have made an impression, because he received a contract shortly afterward. Connie was over the moon, but his happiness was cut short by Germany declaring war in 1914.

Some sources say he was drafted, others that he enlisted, but when he was a little less than a month shy of turning 22, Connie was one of the many young men in Germany sent to basic training. Almost immediately after being deployed to the eastern front, he became seriously ill, and even though he eventually recovered he was still deemed "unfit for service". He was sent to Libau, to the little repertory theater there where they performed a variety of shows to entertain the soldiers. It was literally theater boot camp, and Connie spent over a year honing his craft with the small company of actors.

In 1916, he was fortunate enough to be sent back to Berlin where he was able to pick up right where he left off with Max Reinhardt's company at the Deutsches Theater, and it wasn't long before the critics started to realize how good he was. He received a particularly glowing review by a well-respected theater writer that helped boost his popularity. More people wanted to see him on stage, and soon the offers from film studios started to pour in. Movies were generally considered low entertainment by theater professionals in the late 1910s. They just weren't taken very seriously as an art form, so the primary reason Connie accepted his first handful of film roles was the paycheck.

His first film of record was a kind of Gothic murder mystery, Wenn Tote sprechen/Der Weg des Todes (1917), which, like so much of his work from the silent era, is now sadly lost. But, despite playing a vast range of characters on stage, film directors and producers relentlessly typecast Connie as villains and various "othered" characters because of his look: intense, tall, gangly, "all arms, legs and long dangling hands". Connie later said, "You see, after they had me under contract, they started wondering, 'Now, how are we going to sell this strange-looking man?' I couldn't be a variety of things as on the stage. I had to be something special, something that could be trade-marked. They decided that, with my appearance, I should be something bizarre. So, by the simple process of elimination, they arrived at the conclusion that I would have to be a villain. And to establish the fact firmly in the public mind that I was a villain, they tagged me 'The Man with the Wicked Eyes.'" (Betty Harris, "Villain By Accident", Modern Screen, June 1941) And so it was to be, at least for the first decade of his on-screen career.

It was around this time, when Connie was 25 and his film career was starting to get some traction, that he met and married his first wife, fellow actor Auguste "Gussy" Holl, and formed his own short-lived production company, Veidt-Film, where he intended to direct and produce films of his own. But like Veidt-Film, his marriage to Gussy didn't last long. The dissolution of their relationship, as told secondhand many years later by Françoise Rosay, is definitely interesting if it is in fact true. Rosay quotes Holl as saying, "I excused a lot of his [Connie's] failings and whims because I loved him. But one day he did something to me that I couldn't forgive. I was singing that evening at a cabaret. I left him home and he told me, 'I invited a few friends; we'll dine while we wait for you.' And it just so happened I had received a new dress from Paris. That evening, after work, I arrived home and what do I see? All these gentlemen dressed as women. And Conrad had put on my Paris dress. At this point, I divorced!" (Françoise Rosay, La Traversée d'une vie. Paris: Robert Laffont, 1974)

This story, and others like it, has taken on a life of its own in the ensuing decades. It's hard to say for certain one way or the other whether Connie was or would have considered himself queer by today's standards. He was certainly anecdotally bisexual, but these quotes mostly came after his death. The fact remains, Connie was a part of the film and theater world in Berlin during the Weimar era, so it's not entirely impossible that he was some variety of queer. It's naïve to flat out deny or ignore his reported bisexuality or potential gender fluidity. He was long-time friends with Marlene Dietrich, naturally, and styled himself as a bit of a dandy and quickly became an androgynous fashion icon for both men and women in the '20s. He wore jewelry and an ever-present monocle, which was practical as well as an outmoded fashion statement being reclaimed in the 1920s by the queer community in Germany and elsewhere. At the absolute very least, he certainly moved in queer circles during the Weimar years.

And in 1919, Berlin sexologist and pioneer of queer studies Magnus Hirschfeld co-produced the film Anders als die Andern, directed by frequent Conrad Veidt collaborator Richard Oswald, one of several sozialhygienisches Filmwerk. These were basically PSA films meant to dramatically illustrate different topical social concerns of the time, e.g. abortion, sex work, homosexuality, etc. Some were exploitative and sensationalized, others were more serious and handled with care. Anders als die Andern called for the abolition of Paragraph 175 which condemned and criminalized same sex relationships specifically between men. The film, one of the very first empathetic portrayals of gay men on screen, received a lot of criticism upon its release, and all evidence of the film was ordered to be destroyed by the Nazis in 1933 when they raided Hirschfeld's Institut für Sexualwissenschaft. Nearly 70 years later, a fragment of Anders als die Andern was found and restored, and now exists in the public domain.

|

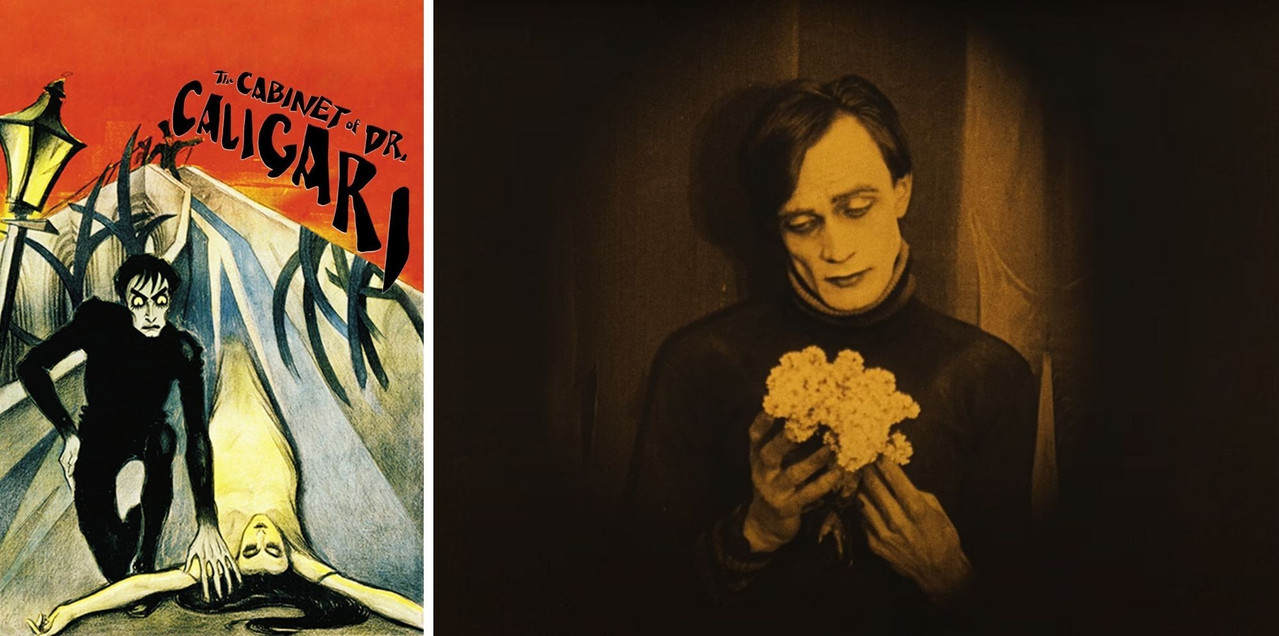

| The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, 1920; Conrad Veidt as The Somnambulist, Cesare |

Rounding out 1919, Connie began production on perhaps the most famous title in his filmography, The Cabinet of Dr Caligari. The film, directed by Robert Wiene, cemented the lasting image we have of Connie today: gaunt, otherworldly, the human personification of German Expressionism. With the arrival of the 1920s, Connie leaned hard into the Expressionist style of acting which suited the dark, nightmarish themes and visuals of the films from this period. The 1920s were Veidt's most prolific decade, and Caligari launched him onto the world stage. He was a movie star.

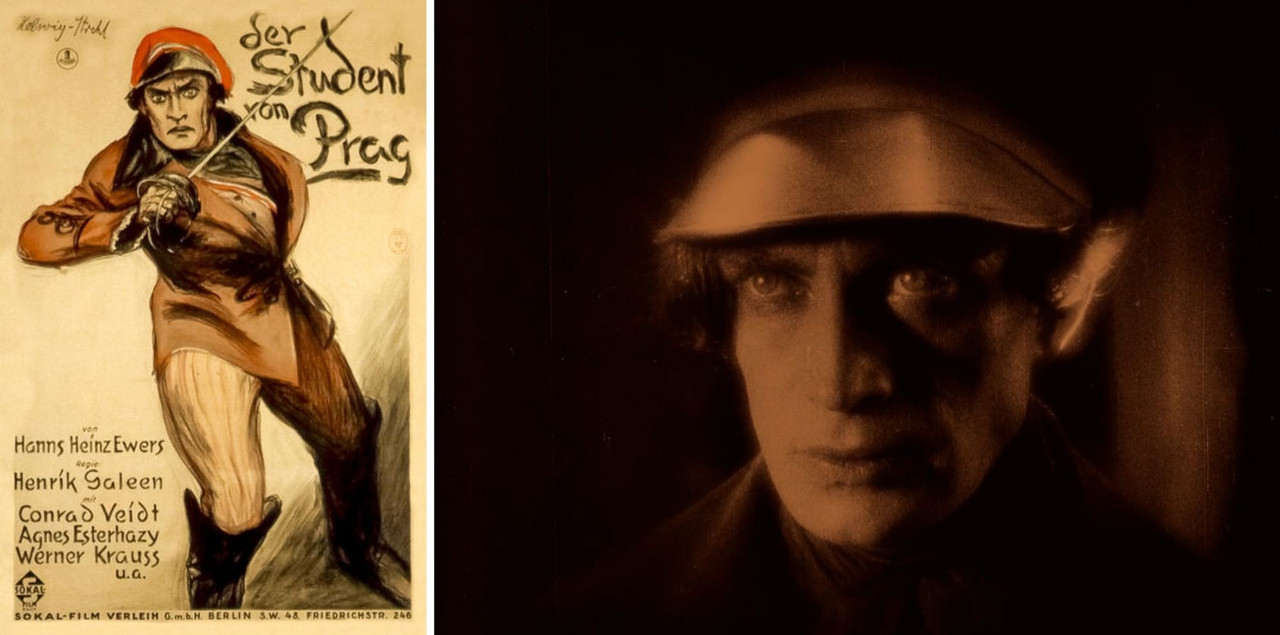

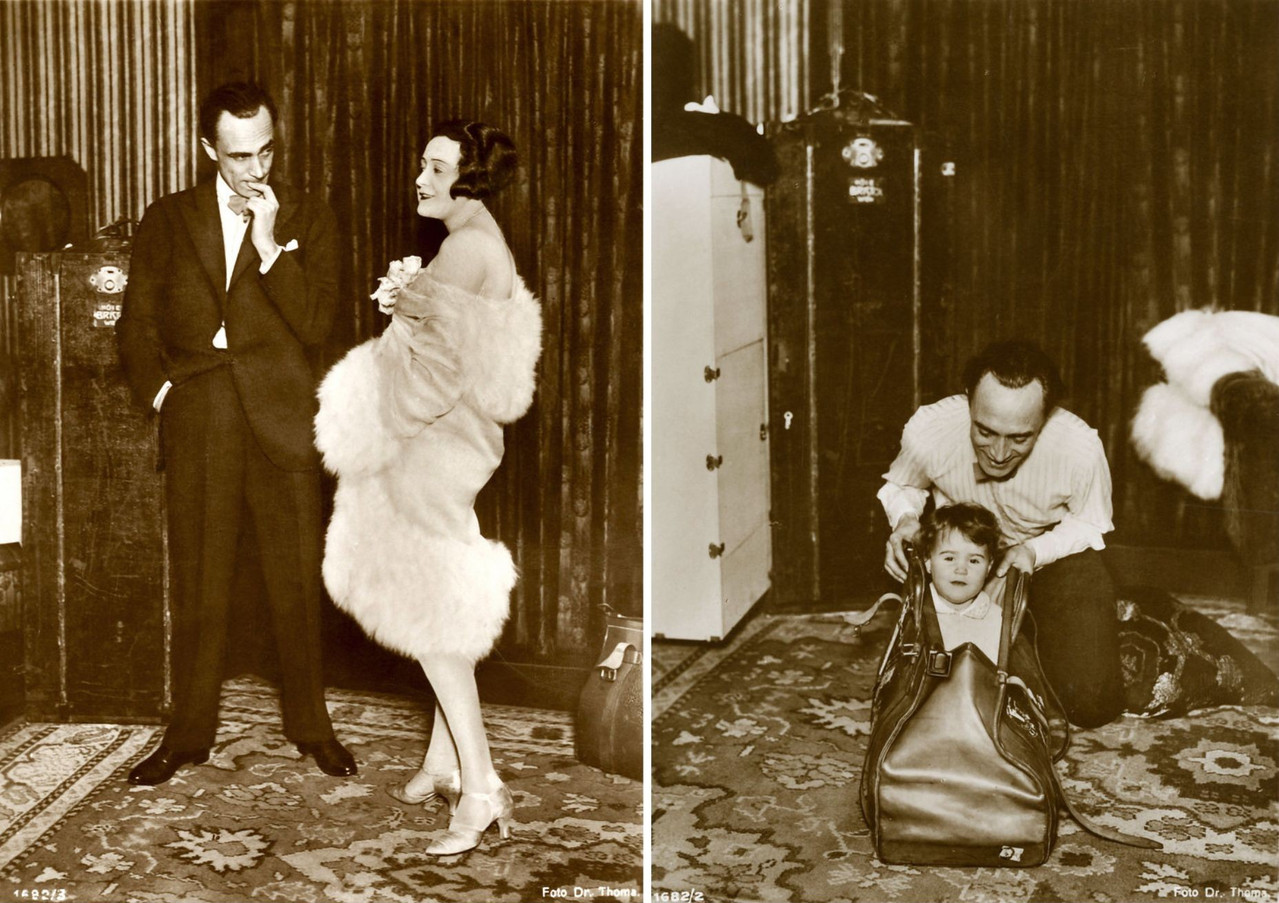

In 1923, Connie married Felicitas Radke and two years later a daughter, Connie's only child, Viola was born. He doted on Viola the way his mother had doted on him. By now he was in his early 30s and considered one of the most popular and talented film actors in Germany. As the decade progressed, the roles he was getting began to change, and Connie's acting technique evolved accordingly. The way he described how he would prepare for a film almost sounds like what we know today as The Method, an evolution of The System made famous in the early 20th century by Russian actor and director Konstantin Stanislavski. Connie's preparation as an actor was deeply meditative; he dove as far as he could into these roles, embodying them both physically and emotionally, on screen and off. His performance as the Faustian Balduin in Der Student von Prag (1926), directed by Henrik Galeen, was groundbreaking at this point in his career. In the film, he is stunningly, Byronically beautiful in a dual role as Balduin and his doppelgänger. Here Connie has the opportunity to showcase his range. He was given room to go big in his performance but also built in quieter moments of surprisingly grounded and heartbreaking vulnerability.

|

| The Student of Prague, 1926; starring Conrad Veidt as Balduin |

But Der Student von Prag was not the picture that got Connie to Hollywood. That was 1924's Das Wachsfigurenkabinett, directed by Paul Leni, where Connie's unhinged performance as Ivan the Terrible really spoke to John Barrymore. Barrymore, a member of 1920s Hollywood royalty, offered Veidt a role in his upcoming film The Beloved Rogue. The project brought Connie to Hollywood for the first time, where he shot just four films between 1927 - 1929, a meager output compared to the frequency of work he was getting in Germany. But perhaps most notably, he teamed up with Leni again for The Man Who Laughs (1928). Connie's poor, tragic character, Gwynplaine, is unfortunately mostly known today for having inspired Bob Kane's design of the Joker in the Batman comic books, which is a real shame, because Gwynplaine is a staggering performance. Connie has to rely solely on his eyes and his body to convey the mutilated boy's grief and shame as the entire lower half of his face is immobilized by a disturbingly exaggerated prosthetic smile.

Despite being contracted to Universal, the studio on the verge of producing their golden age of iconic horror films, Connie had a hard time finding suitable roles in the late 1920s in Hollywood. As sound technology was becoming commonplace in filmmaking, and although he was one of the few silent film actors to eventually successfully transition to "talkies", returning to Germany was really Connie's only option at the time. His English was bad enough in 1929 that he had to decline the offer to play the title role in Universal's upcoming screen adaptation of Dracula. His career in Hollywood was effectively over, at least for the time being.

|

| Connie with Felicitas and Viola, c. 1927 - 1928; photo by Dr Thoma |

Connie immediately jumped back into film and theater work as soon as he got back to Germany. And right away, a number of changes took shape. Once sound recording allowed Connie to use his voice, his roles became more diverse. He was no longer being primarily cast as the creepy or nefarious villain. Now he was getting to play complicated protagonists, quirky romantic heroes, doomed military captains, rascally monarchs, and more. It was clear Connie's time in the theater had given him as much precise control over his voice as he had of his physicality. His vocal quality, pitched a touch higher than one might expect, set him apart from other actors in the 1930s, especially when he started accepting roles in English-speaking films. The standard vocal delivery for actors in Britain and America in the early 20th century was extremely affected, with the British being more reserved and the Americans more animated. But Veidt's use of voice was varied and expressive in a way few others could match at the time.

1932's Rome Express, with its international ensemble cast, was Connie's first British film. He was given a contract with Gaumont British, where he was able to start rebranding himself in another series of very different roles. The British studio continued to cast Veidt as a leading man, further distancing him from the bizarre and otherworldly characters he was playing just a few years before. It just goes to show how big of an international star Connie was in the early '30s that he was able to go from headlining German films to headlining English films. Throughout the decade, he was allowed to play villains, heroes, and morally complex characters alike.

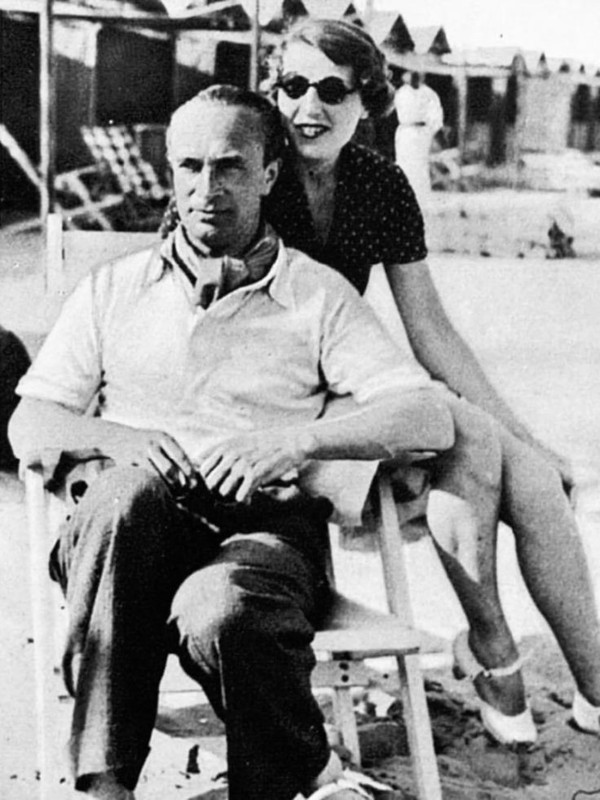

But success often comes with its own complications. In 1932, Connie and Felicitas divorced amicably. The separation,which was still really rough on Connie, was mostly due to his increasingly busy filming schedule and being away from home so often, though it broke his heart to spend less and less time with his daughter. Felicitas and Viola eventually relocated to Switzerland, and Connie and Viola were able to enjoy occasional visits together during holidays and breaks between shooting.

1933 marked the end of the Weimar era, although German art and film had been gradually becoming more conservative and nationalistic for some time. That spring, Connie married restaurateur Ilona "Lily" Prager, and they would stay together until his death. But because Lily was Jewish, they made the difficult decision to permanently leave Germany, moving to England shortly after getting married. There's a story with conflicting information about some exit paperwork Connie was required to fill out; the Nazi-run film industry demanded that an explanation for his departure, and on this exit form in the corresponding field, Connie simply wrote "Jude". He himself was not Jewish, of course, but he was plainly willing to align himself with Judaism if it meant staying with his wife and spitting in the face of Nazis. He and Lily managed to get out right as Germany reached the point of no return.

|

| Connie & Lily on holiday in 1937 |

Later that same year, however, he had to return to shoot William Tell, his last contracted film in Germany. Another film, Jew Süss -- where Connie was set to play the lead, a complicated and fascinating Jewish aristocrat -- was scheduled to start shooting in Great Britain right after William Tell was supposed to wrap. But Connie didn't arrive back in England when he was supposed to. In fact, he was effectively disappeared until he sent a strange, uncharacteristic letter not to Lily, who was naturally extremely concerned, but to Gaumont British producer Michael Balcon. What had apparently happened was that Nazi leadership was outraged at Connie. At this time he was considered both a traitor to the Fatherland and a hugely popular movie star in the pantheon of great contemporary German actors. The fact that he was playing Jewish characters with nuance and complexity, in both Jew Süss and the previous year's The Wandering Jew, got so deep under the Nazis' skin that they threatened an international scandal. There are further details of this incident in Jerry Allen's book, From Caligari to Casablanca, but it's not clear where Allen got his information. If his version of the story is to be believed, Hitler himself basically sent a memo to the William Tell set saying Connie absolutely had to turn down the role in Jew Süss. Connie of course flatly refused and was subsequently detained as punishment. According to Allen, Connie wasn't officially put under arrest but was kept under guard in a hotel and not allowed to leave or communicate with the outside world. Apparently Connie endured verbal abuse, threats, interrogations, isolation, and sleep deprivation. From this version of the story, it's not explicitly stated how much time had passed between his last day of shooting William Tell and when Balcon received the letter which also included a note from a local doctor claiming Connie had fallen ill while in Germany. Balcon and Lily thought the letter and Connie's absence were alarmingly unusual, so together with the British Foreign Office, they sent a doctor to where Connie was being held. The British doctor saw that Connie was perfectly healthy, but even still they had to jump through a number of legal hoops and red tape to get him back to England. The Nazis didn't want this debacle to make international headlines, so they pretty quickly acquiesced to Connie's release. While the details of this story are up for debate, it is obvious that Connie was willing to prove his integrity and resolve through his work, making the choice to stand by his values rather than forsake them the way so many of his well-known German colleagues did. And if there was any vindication at all, William Tell was a major flop.

Once safely back in England, Connie's Gaumont British roles continued to be both challenging and rewarding. 1935's Passing of the Third Floor Back is often included among Veidt fans' favorite films. Connie plays The Stranger, a nameless and mysterious tenant at a London boarding house. The other residents are all extremely troubled individuals, but his ethereally comforting presence helps them begin to resolve their various interpersonal issues. Connie not only stands physically head and shoulders above the rest of the cast, but his restrained, quiet, introspective performance is years ahead of its time.

Toward the end of the 1930s, he signed a contract with powerhouse producer Alexander Korda, and once again suddenly struggled to find suitable parts. A series of flops sent him to France to do a few films before returning to England to team up with writing-directing duo Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. In 1939, shortly before the UK declared war on Germany, Connie and Lily became official British citizens. His first picture with Powell and Pressburger, WWI espionage thriller The Spy in Black, had been released earlier that spring. Tensions with Germany had a massive impact on the British film industry, not only on production but the kinds of stories British filmmakers were telling. The Spy in Black is significant because, on the eve of war in reality, Connie was playing a German character with great depth and dimensionality. His character, German U-boat captain Ernst Hardt, is written and portrayed in a way that is meant to illicit empathy from the audience. In the film he's charming, he's funny, he's duty-bound and tough, vulnerable and clever. It's a great first outing for the Archers and it planted the seeds for Connie's next collaboration with Powell and Pressburger along with costar Valerie Hobson, Contraband. Released in 1940, Contraband is more clearly meant to be a propaganda film, but it's also a playfully subversive romantic comedy. Connie plays a neutral Danish cargo ship captain who gets wrapped up in Valerie Hobson's antifascist spy games during an enforced London blackout. Contraband was truly a collaborative passion project for Connie, and was the film that eventually brought him back to Hollywood.

|

| Stills from The Spy in Black (1939) and Contraband (1940) |

Still contracted to Alexander Korda, Connie's last film in Great Britain was The Thief of Bagdad, his only film shot in color. Like a number of the new Technicolor super productions, The Thief of Bagdad had multiple directors, six in total, not all of whom were credited. The film was plagued with problems and took much longer to shoot than usual, due not only to the scale of the project but also the outbreak of war. Michael Powell said later that Connie was genuinely unhappy on Thief, so much so that he recommended that Korda bring in Powell, since the two already had an established and successful working relationship. But ultimately the film, while a being spectacle intended to compete with Hollywood's recent large scale Technicolor marvels like Gone With The Wind and The Wizard of Oz, suffers from the limited resources available during the early days of WWII.

From Powell's and others' behind the scenes stories, it appears that Connie's professional priority was first and foremost the film itself, making sure the final product would look decent. He would be sure to speak up if things were going sideways. He would also check in with his costars, especially the more inexperienced ones, to make sure they were comfortable. It sounds like there was zero competition on set between Connie and other actors, but he would then turn around and call out directors and other crew members, sometimes going over their heads to voice his concern if need be. This was probably not the most appropriate behavior, but Connie had been making movies for nearly 25 years at this point. During that time, he had made it his business to learn the complicated technical ins and outs of cinematography on top of honing his acting technique, and so made it clear to his producers and directors that he really thought he knew what was best for a picture.

However, it was during production for The Thief of Bagdad that Connie saw his daughter for the last time, shortly to be separated forever by war and by an ocean. Since her parents' separation, Viola had always spent a couple months out of the year visiting her father and vice versa. After a summer visit to London in 1939, during what was the scariest period in their shared history, they parted tearfully at the train station one last time.

1940 brought the release of Contraband, and Connie and Lily sailed to New York to promote and distribute the film in America. While there, he received an offer for a role in MGM's thriller Escape. He was asked to replace Paul Lukas as the villain and to play for the first time, and sadly not the last, a Nazi. This role set Connie up to be typecast to a degree he hadn't experienced since his early career. During the early 1940s, he was generally underutilized by Hollywood with a few shining exceptions. Audiences loved him in everything he did, but the American film studios were at a disappointing loss for what to do with him.

Now back in Hollywood, the bulk of Connie's earned income was donated to British war relief, something he started doing while still living and working in the UK. He especially made sure his money and resources were going directly to children displaced or otherwise affected by the war. Both before and after he moved back to Hollywood, Connie and Lily provided temporary housing for a few different kids who were forced out of heavily bombed areas of England. They also made efforts to help relocate friends, family, and former colleagues who had become refugees in Europe to neutral or allied countries. As a relatively private person, Connie would deflect when asked about his philanthropic generosity in interviews. He would say, "It's only what we're all doing." He wasn't looking for public praise for doing the right thing, he just did it.

After Caligari, Connie is perhaps most well-known for his smallish part in Casablanca (1942) if only because the film has been deemed a classic. His performance isn't really worth writing home about; his portrayals of Nazi villains are decidedly and perhaps consciously lack luster. He hated the Nazis, after all, and having experienced their tactics and threats first hand, it's possible he wanted to make it painfully obvious to American audiences and film studios how dangerous the Nazis were, to cast them in the most authentically disparaging light possible. These performances are not caricatures, but neither are they particularly noteworthy in an otherwise incredible and diverse career. Connie may have agreed to be cast in these less than desirable roles, but it was deeply important to him that there was no way a Nazi could be seen as anything other than deplorable and unsympathetic.

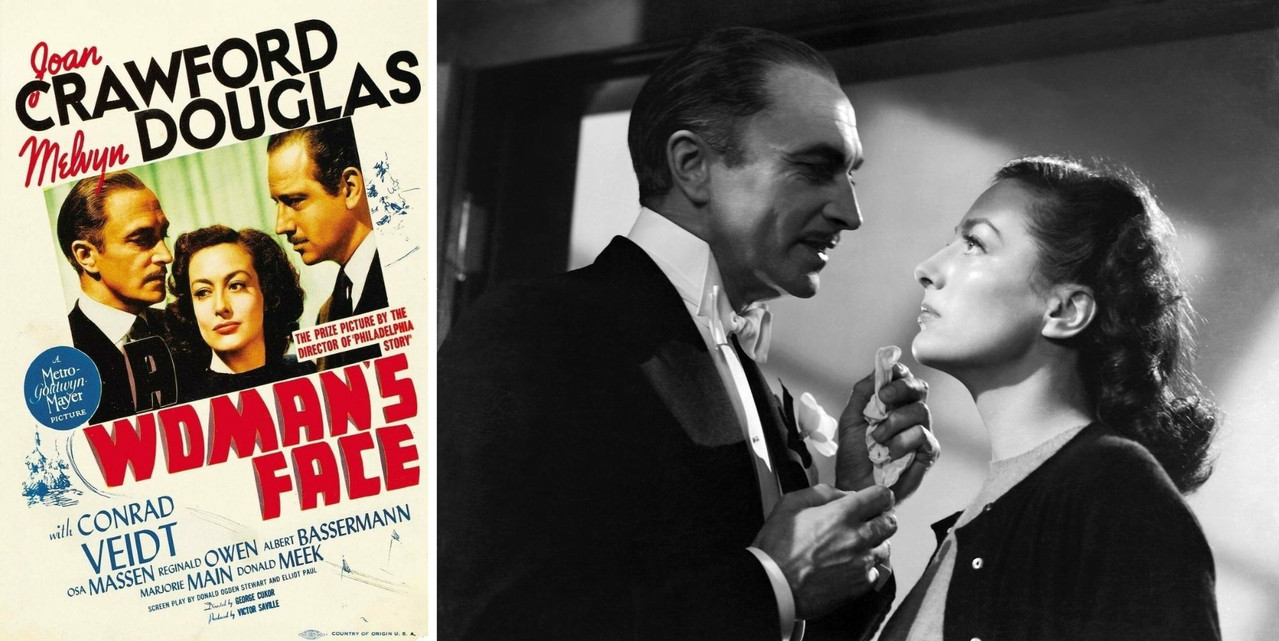

The north star of Connie's late career films in the 1940s, of which there are only eight, is his performance in George Cukor's A Woman's Face. His character, Torsten Barring, enthusiastically described by Connie himself as "Lucifer in a tuxedo", is positively nasty in the absolute best way. He even very nearly steals the movie from its star, Joan Crawford, genuinely at her best as the physically and emotionally scarred Anna Holm. A Woman's Face is considered by fans one of the best examples of everything in Connie's acting toolbox with a wicked twist of camp. You simply can't take your eyes off him.

|

| A Woman's Face, 1941; starring Conrad Veidt as Torsten Barring |

Writers at the time would always stress how unlike Connie was in reality from his film roles. He was always described by journalists, friends, colleagues, etc. as effusive, generous, sensitive, and kind. Both men and women would call him outrageously, breathtakingly attractive, colorfully describing his eyes and voice, often at great length. By all reports, he was engaging, surprisingly funny, and an incorrigible flirt. He loved his pets, was great with kids, remained exceptionally kind to his fans and respectful to women. He was obsessed with cars and golf, and liked spending time outdoors either leisurely enjoying nature or just lazing around his own backyard. He was an avid reader, and had a weakness for sweets and cigarettes. He described himself as a homebody, but was also the perfect party guest, well-mannered and casually elegant, always preferring neck scarves to ties. Remarkably, Connie was never caught up in industry scandal or gossip, and dreamed of moving to the country one day, to live a quiet life.

Connie was also among the Hollywood stars of the early '40s doing featured spots on radio programs to encourage Americans to purchase war bonds. In addition to two radio versions of A Woman's Face, he did a bizarre 1942 radio play called "Return to Berchtesgaden", essentially a WWII version of A Christmas Carol where Hitler is visited by literal ghosts from his past. Connie as one of the phantoms delivers a chilling and intense late career vocal performance. Also worth mentioning is 1942's Nazi Agent. Connie, no stranger to playing opposite himself, plays identical twins: Hugo, a Nazi scumbag diplomat, and Otto, a kindly former professor turned bookshop owner. On its face, the movie is just another piece of war propaganda, but it also has some interesting things to say about American-German/immigrant identity during that time in history, and it allows Connie the chance to play the lead, a hero, for the one and only time in his films of the 1940s. He carries the film with a wonderfully gentle realism.

|

| Nazi Agent, 1942; starring Conrad Veidt as Otto Becker and Hugo von Detner |

Connie's mother had died in 1922 of a heart condition, something she unfortunately passed on to her son. Medication alone wasn't enough to treat Connie's ongoing illness, and it was kept out of the press until after his death. His final film, Above Suspicion (1943), allowed him to be silly and eccentric in a heroic supporting role, a blessing after the previous year's Casablanca. But Above Suspicion was to be released posthumously as Connie tragically died suddenly of a heart attack on April 3rd while out golfing with friends. He left behind an estate of $72k to Lily and Viola, which would be about $1.3M today. He was eventually cremated and Lily's ashes were added to his after her own death 37 years later. But the story of their remains is a strange one and worth further reading.

So, what if anything is left of Conrad Veidt's legacy in the 2020s? One hopes it's "courage, integrity, humanity", the motto of the Conrad Veidt Society, founded in the 1990s. Or maybe it's in all good works done without the expectation of receiving anything in return. Maybe it's something that can be seen in the work of other actors further into the 20th and 21st centuries, if you know where to look. But really he stands alone, both literally and figuratively head and shoulders above his peers. A lot of his performances are timeless, even his more stylized and expressionistic work of the early 1920s, but especially his starring roles in the 1930s and '40s. Throughout his 100 plus film career, Conrad Veidt set an impeccable standard of professionalism as an actor while also being a wholly decent human being. His death robbed the world of his talent, generosity, and what could have been an even greater legacy in film history.

RESOURCES:

- Conrad Veidt On Screen, John T. Soister; biography, Pat Wilkes Battle

- Conrad Veidt: Ein Buch vom Wesen und Werden Eines Künstlers, Paul Ickes

- Conrad Veidt: Lebensbilder, ed. Wolfgang Jacobsen

- "Was Prominente als Kinder werden wollten", Neues Wiener Journal, 27.03.1932

- "Wir und das Theater", herausgegeben von Walter Firner, München, 1932

- "The Story of Conrad Veidt", Sunday Dispatch, 10-11.1934

- Vertigo, Harald Jaehner

- Michael Powell's tapes on the Criterion Channel

- LA Times, 21.06.1943

No comments:

Post a Comment